What It Means to Be a Filmmaker

An anchor essay on authorship, craft and care in modern filmmaking. Exploring how Kumo London’s filmmaker-first ethos keeps storytelling human by Yohan Forbes.

There’s a pause before the first take, when the room holds its breath. That silence is the truest part of filmmaking, the moment before performance, before intention hardens into action. It’s where the work really begins.

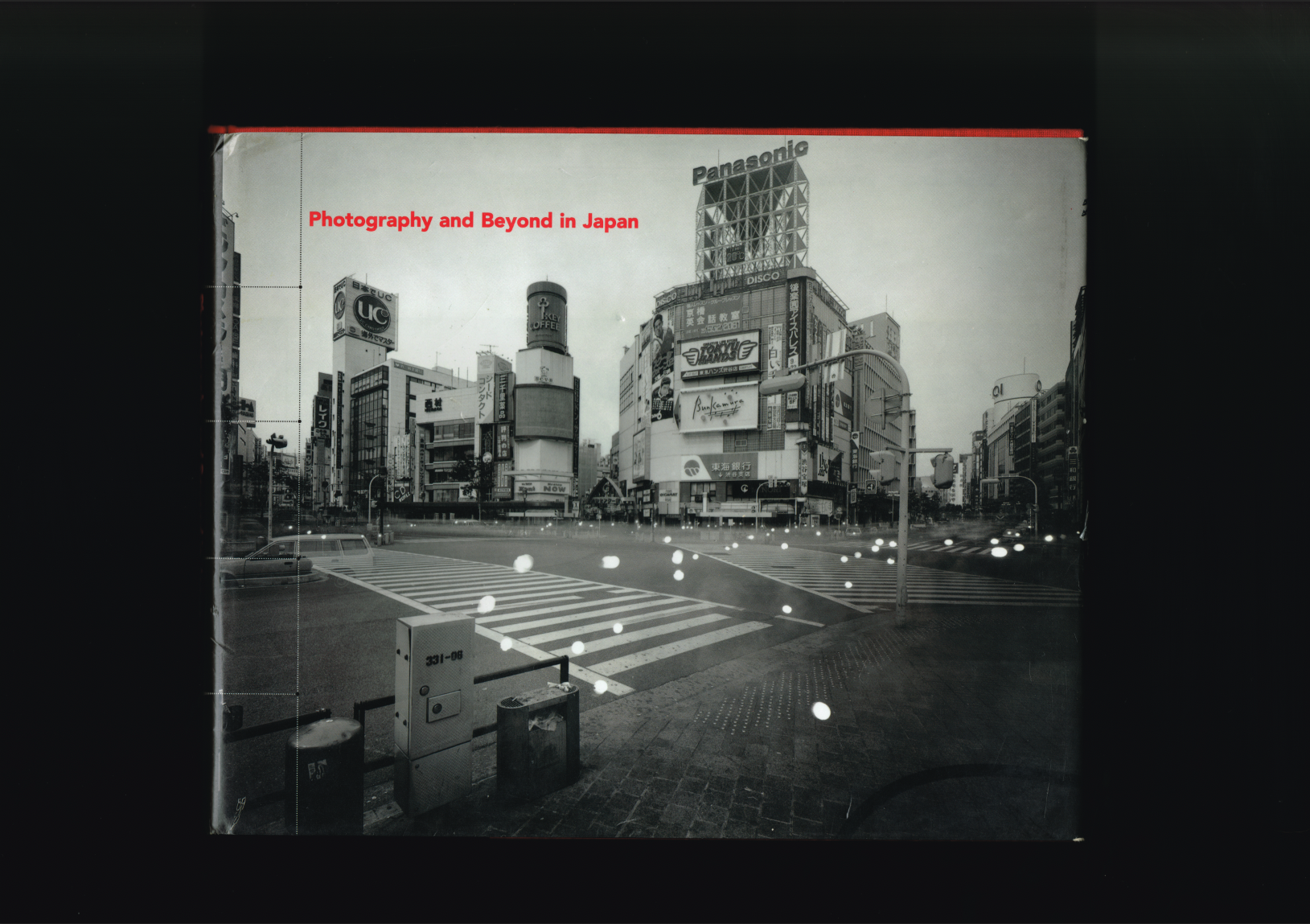

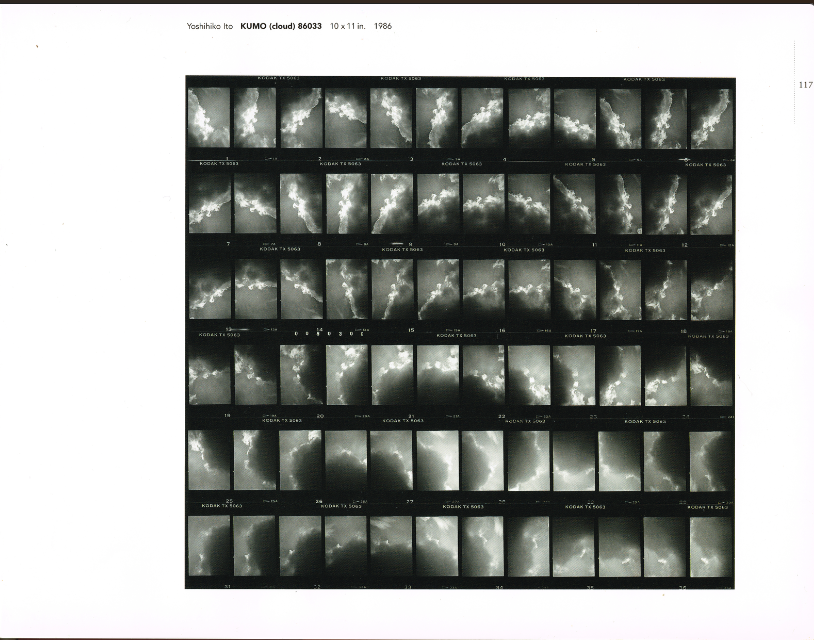

One of the earliest references that taught me to look differently came from a book called Photography and Beyond in Japan. Inside it, I discovered Yoshihiko Ito’s photographic study Kumo (Cloud) (1986), a grid of skies captured frame by frame, each image holding a slightly different texture of light. The work was simple but precise; it asked nothing more than to see. That stillness stayed with me. It reminded me that filmmaking starts in the same place; in observation, in attention, in learning to notice what shifts even when nothing seems to move. The name Kumo became a quiet guide for my own practice: a reminder that to film is to watch, to wait and to translate the invisible air between moments.

Being a filmmaker isn’t a job title; it’s a way of seeing. It’s the choice to look closely at what others pass by, and to keep caring when it would be easier to detach. The craft isn’t just about light or composition or pacing; it’s about presence and awareness, the courage to stay awake to what’s in front of you and to remain true as you continue to learn.

The Beginning of Seeing

I never set out to be a filmmaker in the commercial sense. I came to it through observation; of people, spaces, rhythm, of the subtle negotiations between silence and speech. The camera became a way to translate what I was already paying attention to: truth, care and consequence.

Film, for me, has always been a form of connection and expression. It’s not about collecting beautiful images, but about asking why something feels the way it does and who that feeling belongs to, how it sounds, how it breathes, how it keeps the audience within the world we translate. The moment you forget that, you stop being a filmmaker and start being a technician.

But being a technician isn’t a failing; it’s a foundation. The technical is what allows the creative to exist. Learning how something works is often the only way to express why it matters. I’ve found that understanding the technical side of filmmaking doesn’t confine creativity; it frees it. It lets you speak fluently with every department, so the craft becomes a shared language rather than a set of isolated tasks. Learn the technical to reach the creative.

Authorship as Care

Authorship isn’t about control or ownership. It’s stewardship, the duty to honour the story, the people inside and behind the frame. The themes they represent and the reason you were asked to tell it, the purpose.

That’s why Kumo is centred around a simple principle: care is craft. The Kumo Collaborative Code exists because production can easily lose it's humanity. We work to keep craft human, to protect credit dignity and the space for ideas, collaboration and purpose to emerge without ego.

At Kumo, authorship means shared authorship. It’s the recognition that a good film doesn’t belong to one person; it’s held by everyone who touched it with intent.

I’ve always stayed through the end credits. There’s something sacred about watching those names crawl, hundreds of them, sometimes thousands, the quiet procession of people who made the experience possible. Behind every star on screen is an army of unseen artists, technicians and craftspeople. Each carries a small part of the film’s weight. Some translate vision into light, others into movement, others into sound. Together they create the illusion of a single voice. Sitting through the credits is my way of honouring that, the invisible collaboration that turns intention into cinema.

That’s what authorship really means to me: not possession, but acknowledgement.

'The film ends, the lights come up and still, you stay, you watch and you remember that art is never made alone.'

Craft, Not Spectacle

Technology has made it easy to make things look impressive. What’s harder and rarer is to make something feel true.

Craft, to me, lives in restraint. It’s in how a window light softens a confession, or how a cut waits just long enough for honesty to land. You can’t fake that timing; it comes from listening.

We apply that same philosophy across everything from branded content to broadcast. Whether it’s Fitbit Versa Playground, BBC Sounds: Jools Holland, or a charity film for SEO London, the same standard applies: technique should serve emotion, not eclipse it.

Leadership as Calibration

Directing isn’t command; it’s calibration. Our duty is to tune energy, to sense when a set needs stillness, when a performer needs reassurance, when a producer needs clarity, when we admit to ourselves that we don't have all the answers. Most importantly, when we can close our eyes and trust in the collaborators around us.

Leadership, in this space, is invisible when it’s working. It’s about protecting calm so others can bring their best. It’s an act of emotional engineering as much as visual design.

I’ve learned that a filmmaker’s authority doesn’t come from volume but from steadiness, from being the quietest person in the room who still knows where the story needs to go.

Why Filmmaker-First Matters

We live in an age obsessed with visibility. Everyone’s producing content, everyone’s chasing reach. But reach isn’t resonance. The audience may not remember the campaign, but they will remember the feeling.

That’s what “filmmaker-first” means at Kumo: it’s not a slogan; it’s a safeguard. It means leading with empathy, not metrics. It means asking what’s true, not what’s trending.

When brands work with filmmakers who think this way, something changes. The work stops shouting. It starts listening and that’s when people recognise themselves in it.

The Ongoing Practice

Being a filmmaker is a continual act of alignment and reflection. It’s between what you make and why you make it. It’s easy to drift into production for production’s sake. But each project, each collaboration is a chance to return to the centre. Every film asks the same question: Are you present? Not just physically, but emotionally. Are you paying attention to the people beside you? Are you using the craft to reveal or to hide?

For me, those questions define the work more than any award or metric. They’re the compass that keeps Kumo moving with intention. To be a filmmaker is to live inside that pause before the first take, listening, calibrating, then protecting the fragile thread between story and soul.

It’s quiet work and maybe if we do it right, the silence before action becomes a silence that stays with the viewer long after the cut.

Read more in The Filmmaker's Statement.